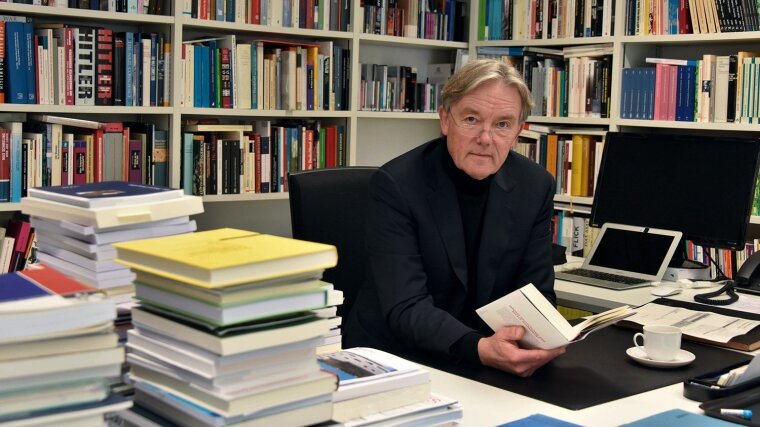

The people of Thuringia went to the polls in late October. After the AfD (»Alternative for Germany«) had won almost a quarter of the votes in Brandenburg and Saxony, the party achieved a similar result in Thuringia: 23.4%. Under the provincial leadership of Björn Höcke, a radical right-winger, the party has become the second strongest political force in the Free State. Two days after the election, we spoke with historian Professor Norbert Frei. His book, »Zur rechten Zeit. Wider die Rückkehr des Nationalismus« (»The Right Time. Against the Resurgence of National Socialism«) was published in February 2019.

Have the people of Thuringia voted for the AfD despite or because of Björn Höcke?

I would like to say that a significant amount of the electorate voted for the AfD despite Björn Höcke and not because of him, but it is hard to make such a statement following the attack on the synagogue in Halle. I was hoping more people would now distance themselves from the party.

The AfD received a quarter of the votes—what does that say about the people of Thuringia?

The election result says something about the general situation in the east of Germany, where voter behaviour is more volatile than in the west. In former West Germany, the socio-moral milieus of the Weimar Republic that had long shaped voting behaviour were largely reconsolidated after the Nazi period. There was no such opportunity in the GDR—the erosion process simply continued.

But that does not explain the election results over the past 30 years.

Since 1990, the east of Germany has been much more willing to experiment than the west of the country. The Liberals have enjoyed major success in Saxony-Anhalt on two occasions, and high results have also been achieved by the far-right political parties DVU and NPD. And in the formerly »red Saxony« as well as in Thuringia, CDU prime ministers held office for many years, although they were mainly chosen for their personality and less as representatives of their party.

Why is East Germany so eager to experiment?

II think it is partly because people are not overly prepared to commit to one party after over fifty years of dictatorial single-party rule. They like to experiment and see what might work. For example, »Die Linke« has long been perceived as a protest party, which is why people voted for them—a role that the AfD has now assumed.

It is striking that almost all the leaders of the AfD come from the west of the country. How do they fit with the voters in the east?

In our book (»The Right Time«), we refer to them as the »Riders to the East«. Some of them—such as Alexander Gauland who, of course, was raised in Chemnitz and only moved to the west in 1959—had worked in and with the CDU. They turned eastwards after German reunification and found a Germany that had long since disappeared from the west.

What do you mean by that?

They see the east as a Germany without all the »evil« related to the country’s struggles to coming to term with its past, without the protests of 1968, and without immigration.

That sounds like a testing ground for the »Riders to the East«?

In fact, even younger people like the publisher Götz Kubitschek see the east as a land that can be moulded in their favour. This is where they can live out their ideals of a white, monocultural Germany that no longer exists in the west. This goes beyond mere protests; they have nationalist and racist transformation ambitions.

Cover of the current book by Norbert Frei and colleagues.

Image: UllsteinYou mentioned the political milieus and the disassociation with such milieus in East Germany. What did things look like in the past?

The political maps from the Weimar Republic amazingly coincide with many regions today. As we know, the NSDAP encountered most difficulties in the strongholds of political Catholicism and the labour movement. By contrast, Nazi propaganda was welcomed much more quickly and enthusiastically in Protestant regions, especially here in Thuringia. Even after 1945, radical right-wing parties found it easier in Protestant regions—and some have remained successful there to this day.

You are a historian, but we would like to ask for your thoughts on the future.

Historians often say it is difficult enough to predict the past! But on a serious note, I was just speaking to a colleague about my concern that the developments in East Germany might just be a precursor for a wave of right-wing populism in the whole country, which we can already see in the rest of Europe and beyond. I believe this is related to the revolution in our communication practices—in short, the destruction of the »bourgeois public sphere«, as Jürgen Habermas would say. But that is just one aspect.

You sound rather pessimistic.

Well, if everything really has become much more fluid, this also gives us a glimmer of hope: Things can change again quickly, so the AfD should not be so sure of its voters. Of course, right-wing hard-liners, racists, and anti-Semites will always be welcome in the AfD, but the party cannot bank on those who have chosen it for a protest vote.

The courts have ruled that Björn Höcke may be called a fascist.

His words certainly justify such a description, and there is no doubt about his ideological proximity to National Socialism. However, a court’s permission to label him a »fascist« is not as important as our duty to pull apart his inhumane slogans and to make clear that none of his positions are truly conservative.

Interview: Katja Bär und Stephan Laudien