Saxony, Brandenburg and Thuringia: Three federal states in eastern Germany have elected their state parliaments in recent months. The AfD (»Alternative for Germany«) has been elected as the second most popular force in all three state parliaments. The xenophobic and populist party questions the fundamental right to asylum, denies man-made climate change, and wants to leave the eurozone. But what makes this party so successful in the east of Germany? The sociologist Katja Salomo provides some explanations.

What makes large swathes of people vote for populist right-wing parties? Sociologists, psychologists, and political scientists agree—they are mainly driven by fear. Fear of globalization, fear of alienation, fear of unemployment. »The common ingredient to all these fears is the idea that people will be worse off and unfairly end up on the losing side in the future,« explains Katja Salomo. The young sociologist is investigating the relationship between such perceived disadvantages and voting behaviour.

»Perceived disadvantages often result in xenophobic and anti-democratic sentiments,« she states. It therefore comes as no surprise that right-wing populists are enjoying particular success in the eastern federal states, where they are presenting their simplistic solutions and political programmes designed to preserve and restore old ways. The feeling of being disadvantaged is mainly derived from a person’s socio-economic situation. The east of Germany suffered an economic downturn after the country’s reunification, leading to the collapse of entire industries, a rapid rise in unemployment, and with it the rise of populist parties.

But according to Salomo, that alone does not explain the current electoral success of the AfD. After all, East Germany has caught up economically over the past 30 years. There are new economic sectors; tourism is booming in many places; and the economic power of the eastern German states falls within the EU average. It can no longer be generally stated that East Germany is economically inferior to West Germany.

The demographic situation in East Germany is extremely precarious

Nevertheless, the situation in the east of the country is extremely precarious, says Katja Salomo. »The demographic situation is more precarious than in almost every other region in the world«. Salomo came to this conclusion in her recent study on the relationship between intolerant and antidemocratic sentiments and the living environments of people in the State of Thuringia. Salomo mentions one of the findings of her study: »If Thuringia were a nation state, it would be the country with the second oldest population—behind Japan«. Furthermore, only six of around 200 states would have a lower percentage of young people under the age of 15, and only nine of the world’s countries would have a similar excess of men aged 15 to 49.

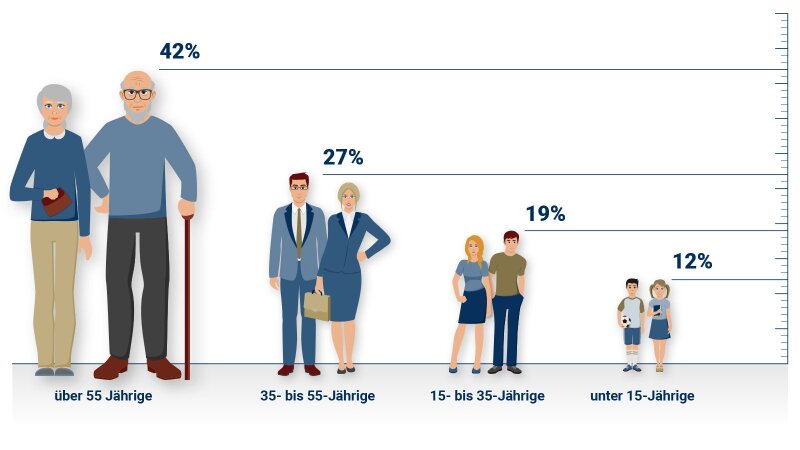

How old are the people of Thuringia? Thuringia has three and a half times as many people over the age of 55 as children and adolescents under the age of 15. (Source: Statistical Office of Thuringia)

Graphic: Macrovektor/freepik»This results in a demographic homogeneity that is unprecedented on both an international and historic level,« says Salomo. This situation may lead to fears of decline and the feeling of being disadvantaged—similar to the economic downturn that was triggered by the country’s reunification. This is particularly evident in rural areas and may explain why right-wing populists have enjoyed so much electoral success there. After all, while the unemployment rate in Thuringia has almost halved since the late 1990s, the ratio of over 50s to under 15s has grown by a quarter in the same period. Thuringia now has almost four times as many people over the age of 50 as children and adolescents under the age of 15.

Katja Salomo can only speculate as to why the perceived quality of life is shaped by the demographic homogeneity of the local population: »Due to the lack of children and adolescents, there is also a lack of leisure activities. When a population shrinks due to out-migration, bus lines are discontinued and shops are closed. There are fewer music events, sporting events, and street festivals—everything that forms the basis of social life,« says the 33-year-old sociologist. The precarious demographic situation is worsened by the fact that an above-average number of young women are leaving the state and resettling in the west. »Women have always been more involved in family life and invest more in neighbourly relations«. However, Salomo emphasizes that the housing and living situation is only one of several potential socio-structural reasons for xenophobia and scepticism about democracy.

Young people are moving away despite low unemployment

Katja Salomo is personally inspired by the fact that she grew up in a small town in East Germany, giving her first-hand experience of many of the developments that she now investigates in her sociological work. German reunification also resulted in an economic downturn in her home town, a Saxon community with around 1,000 inhabitants. But even here, the economic slump was followed by continuous growth, a decline in unemployment, and the neat renovation of streets and houses. »But life was missing,« says Salomo. »And things have remained that way. There are only a few bus lines, so you can hardly leave town at the weekend and there is absolutely nothing for young people to do,« she recalls. No cinema, no youth club, no sports facilities. »It is frustrating. If you can move somewhere else, you don’t look back.«

Soziologin Katja Salomo stammt aus einer 1.000-Seelengemeinde in Sachsen.

Image: Anne Günther (University of Jena)But how can politicians in Thuringia, Saxony and other eastern German states combat the out-migration of their people and the feeling of being disadvantaged? Katja Salomo’s solution may seem somewhat paradoxical at first glance: »They have to ensure that people, especially young people, can get out«. The most important thing politicians can do for rural areas is to invest in sustainable mobility: »So those who are too young or old to drive also have the opportunity to take part in social and cultural life«. In the end, it is yet another economic matter: »Money has to be spent on expanding bus and train networks«. Nevertheless, the sociologist from the University of Jena predicts the further out-migration of people from East Germany and the continued ageing of the local population. She believes the problem can only be addressed on a national level, as those leaving East Germany are mainly resettling in the west of the country. »East Germany has been demographically helping the west of the country by providing a stream of young and educated people over the past 30 years,« says Salomo. But the ageing of the population cannot be stopped in the west either. »The future of the west is already reflected in the east«. It is time to prepare for it.

By Ute Schönfelder