Volunteering is held in the highest regard. After all, those who voluntarily support others show community spirit and responsibility. 40% of Germans are involved in voluntary work—and this figure is on the rise. Yet, sociologists Prof. Dr Silke van Dyk and Dr Tine Haubner are critical of the volunteering boom. Even voluntary work has a dark side.

Collecting clothing donations, helping children with their homework, looking after dementia patients, accompanying refugees to the public authorities—more and more people in Germany are working for a good cause on a voluntary, unpaid or low-paid basis. »This, of course, deserves recognition and is very fulfilling for many people,« says Prof. Dr Silke van Dyk. Nevertheless, the sociologist at the Friedrich Schiller University criticizes this phenomenon, arguing that the state is unlawfully exploiting the work carried out by volunteers—especially in the social sector. Van Dyk further summarizes the problem: »Voluntary work is often not so much of a voluntary choice, especially when volunteers have to rely on allowances to cover their expenses«.

State-sponsored shadow economy

Researchers have been observing profound socio-economic change for several years. While in previous decades the state and and economy could rely on the fact that women would take care of the household and children all day for free, women are now generally employed. There are nowhere near enough childcare facilities or elderly care services for family members; and so it is unclear who will take care of the tasks that were formerly family duties assumed entirely by housewives. Considering the demographic developments in Germany, these tasks will only increase. According to Dr Tine Haubner, volunteers are often the solution.

In principle, voluntary work is perfectly acceptable, she says, but when central central public services are carried out by volunteers who do not get paid or only receive an allowance to cover their expenses, we run the risk of informalizing and de-professionalizing the sector. »We can certainly refer to the situation as a state-sponsored shadow economy,« states Van Dyk, »because the lines between voluntary work and low-paid employment are becoming increasingly blurred«.

A growing number of volunteers are being lured into the social sector through financial incentives—albeit below the minimum wage and labour law standards. Van Dyk lists some examples: »There are cash benefits provided to those who volunteer in the elderly care sector; there is a flat-rate allowance for exercise instructors and those working an honorary capacity; and people who participate in the Federal Volunteer Service are compensated for their expenses.« The problem is compounded by the issue of professionalism. If volunteers teach German and provide legal advice to refugees, this poses a serious question as to the quality of the services. The situation in the elder care sector is particularly controversial, highlights Haubner, who researched the exploitation of untrained caregivers in Germany for her doctorate. »Older women in particular complement their modest pension by volunteering in households with care-dependent persons«.

There may be a clear distinction between the tasks assigned to volunteers and those assigned to professional nursing staff, but their roles constantly overlap in practice, such as when volunteers not only take a walk in the park with patients, but also help them go to the toilet or take their medication. »Responsibilities are not monitored in in households with care-dependent persons, so volunteers often fill the gaps that emerge in the world of elderly care marked by a shortage of skilled workers and time pressure,« says Tine Haubner.

Food banks—the poor are helping the poo

This type of shadow economy is creating double structures in the areas where there is a lack of initiatives offered by the welfare state: The professional services provided on the regular labour market are used by those who can afford them, while those without the necessary funds have to rely on the work of volunteers. While volunteering and honorary work have historically been carried out by the middle classes, the researchers are currently observing a phenomenon referred to as »the poor helping the poor«. The best example of this are the food banks where donated groceries are distributed to people in need. Those who volunteer here often depend on the food banks themselves, such as long-term unemployed and poor pensioners. »We are seeing that people from the secondary labour market who find employment at food banks through support measures do not make the transition to the primary labour market; they stay here as volunteers, often in the hope of further measures and because the work gives their lives structure,« says Silke van Dyk.

Van Dyk and Haubner have revealed further negative aspects of voluntary work throughout their ongoing study, which they are conducting alongside their colleagues Dr Emma Dowling and Laura Boemke. They are comparing types of volunteering and honorary work in East and West Germany—specifically in the federal states of Baden-Württemberg and Brandenburg. »When it comes to volunteering and honorary work, East and West Germany are still worlds apart—even 30 years after the fall of the Berlin Wall,« states Tine Haubner.

Besides the fact that—unlike in East Germany—the traditional and charitable housewife can still be found in great number amongst the middle classes of Baden-Württemberg, voluntary work is generally well respected in southwest Germany. This is not the case in Brandenburg, where voluntary work happens close to the labour market: People are drifting between the low-income sector, voluntary work and employment office measures, or they are complementing their unemployment benefits through work in the Federal Volunteer Service. 75% of volunteers over the age of 27 are long-term unemployed persons, so it comes as no surprise that volunteering has a different meaning in Brandenburg than in Baden-Württemberg. While in Brandenburg volunteering is often regarded as »working for free«, most volunteers in West Germany find it important that voluntary work is unpaid. »Voluntariness also means freedom and independence,« says van Dyk. This sentiment is hardly expressed by anyone in the East. »The people here take a more pragmatic approach—if you work, you deserve to be paid«.

The sociologists at the University of Jena have observed a particularly unsettling trend in rural areas in Brandenburg, where many people who are volunteering to help refugees are doing so in secret. »They do not talk to their neighbours or colleagues about it, and they do not go to the reception centre in their own car,« reports Silke van Dyk. They fear attacks and hostility from xenophobic, right-wing extremists and have often experienced such attacks.

Voluntary work provides space for civil society to thrive

In spite of all these problems, van Dyk and Haubner are not calling for the restriction of voluntary work by any means. »As a society, we need the obstinate and sometimes even rebellious form of voluntary work. We do not want a 100% state-regulated world; we need a space in which civil society can thrive«. Nevertheless, it is important to make a clear distinction between voluntary work and the responsibilities of the welfare state—for the protection of those who rely on the benefits guaranteed by the state, and for the protection of voluntary work itself.

By Ute Schönfelder

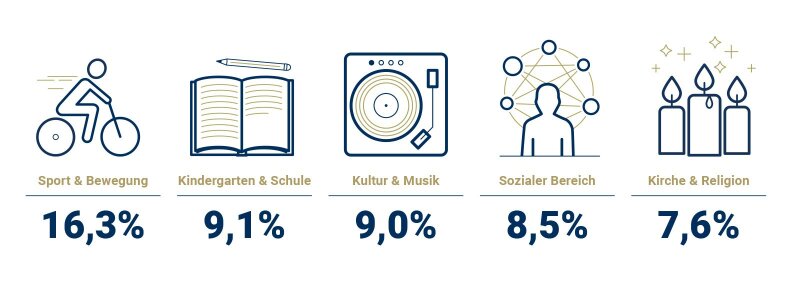

In which sectors do Germans volunteer? These figures indicate the proportion of the total population in Germany aged 14+ who work as volunteers in different sectors. (Source: German Volunteering Survey of the Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth).

Picture: Liana Franke