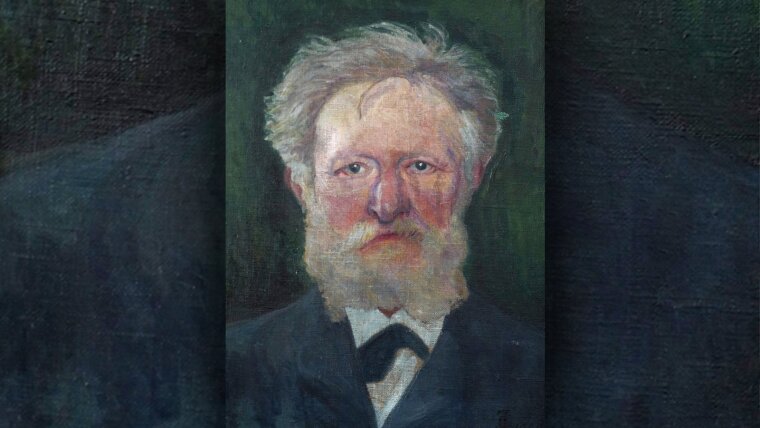

Rudolf Eucken arrived at the University of Jena 150 years ago. A Professor of Philosophy, Eucken lectured in Jena from 1874 to 1920 and was held in high renown, especially abroad. In Jena, however, the prevailing mood when Eucken won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1908 was one of scepticism—not least from Ernst Haeckel, who would have liked to receive the prize himself.

By Sebastian Hollstein

Some famous authors receive the Nobel Prize in Literature as the crowning achievement for a lifetime of work. Other authors receive this award and achieve a new level of popularity, leading to their discovery by a wider audience. And, then, there are authors who are famous for winning the Nobel Prize, even though nobody seems to know why. Rudolf Eucken belongs to the latter category—and is the University of Jena’s only Nobel Prize laureate to date.

In 1908, the selection committee awarded Eucken the Nobel Prize »in recognition of his earnest search for truth, his penetrating power of thought, his wide range of vision, and the warmth and strength in presentation with which in his numerous works he has vindicated and developed an idealistic philosophy of life«. Yet, Eucken was not the committee’s first choice. Instead, he was the compromise, because the selectors could not choose between Swedish author Selma Lagerlöf and English poet Algernon Charles Swinburne. (Lagerlöf received the Nobel Prize the following year, while Swinburne died in April 1909.)

Answers to the crisis of modernity in 1900

Despite this restriction, Rudolf Eucken was far from an emergency, makeshift solution. Eucken and his works were very popular at the time, particularly outside of Germany. His books had been translated into English since 1880, followed by other languages, and engaged a global readership. In works such as »Die Lebensanschauungen der grossen Denker« (The Problem of Human Life as Viewed by the Great Thinkers) and »Der Kampf um einen geistigen Lebensinhalt« (The Struggle for a Spiritual Content of Life), which appealed to and reached a wide audience, Eucken examined how spiritual life could keep pace with the world’s modernization.

He strived to find philosophical answers to the crisis of modernity at the turn of the 20th century. »It was necessary to free modern life from the serious lack of truthfulness from which it suffered and promote an internal enhancement, a radical change in the state of human life,« he recalled in his memoirs, which were published in 1921.

His ideas were shaped, above all, by certain visions and philosophies of the world and life. In a new form of idealism, he brought naturalism and intellectualism together and combined them with a form of activism which gave expression to spiritual life and enabled self-determination. Eucken believed that in addition to their work, each person should ensure their life held a spiritual purpose.

Although his ideas were well received and acknowledged with the Nobel Prize, Eucken also faced repudiation, even at his own university—from his friend and intellectual adversary, Ernst Haeckel. An evolutionary biologist, Haeckel had coveted the Nobel Prize himself. In fact, he had heard rumours that the Nobel Prize would be heading to Jena and assumed he was the only possible recipient.

»Exactly how it should be awarded to my principal adversary, Eucken, is a mystery to my colleagues here! He is a good orator and a devout Kantian [...] and has written a number of ›nice books‹ about ›higher aims‹ and so on, but he has not produced a single original work of value!« wrote Haeckel in a letter to a publisher friend, outing himself as a poor loser—even though, in truth, he was never in the running.

The cultural epicentre of the city

Prior to winning the prestigious award, Eucken and Haeckel had become figureheads for the University of Jena around 1900. Born on 5 January 1846 in the East Frisian town of Aurich, Eucken was a philosopher from humble origins. His brother passed away when he was five years old, followed shortly after by his father, a postman. In 1863, Eucken embarked on studies in philosophy, classical philology and ancient history in Göttingen. After securing his doctorate, he taught at grammar schools in Berlin, Husum and Frankfurt am Main, before eventually accepting a position at the University of Basel in 1871. As the small family’s finances required them to live in a single household, Eucken’s mother accompanied him through these relocations until her death in 1872.

In 1874, Rudolf Eucken was awarded a Professorship in Philosophy at the University of Jena. He settled in Thuringia and raised a family with Irene Passow who was 17 years his junior. The couple married in 1882. The guests at their wedding included the crown prince—future short-lived emperor Frederick III—, who had studied with the bride’s late father. The Euckens acquired a villa in Jena at what is now Forstweg 22, which soon become a hub for international students and academics— as well as a social and artistic hub of the city. Writers including Stefan George and Hugo von Hofmannsthal, painters such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde, and musicians like Max Reger all visited at one time or another.

Irene Eucken, a painter herself, served for a period as Managing Director of »The Art Lovers’ Society of Jena and Weimar«. She played a significant role in commissioning Swiss artist Ferdinand Hodler to produce a painting for the auditorium of the new University Main Building in Jena in 1907. The youngest son of the Eucken family—Walter, who became an economist—is immortalized in Hodler’s work, entitled »Departure of German Students to the War of Liberation in 1813« (see image,right). Hodler stayed with the Euckens for a period in early 1908 to conduct initial studies in Jena for the commissioned work, during which time Walter posed as a model for the soldier putting on a jacket in the centre of the piece.

The »Departure of German Students to the War of Liberation in 1813« by Ferdinand Hodler (1853–1918) displayed in the auditorium of the University of Jena.

Image: Jan-Peter Kasper (University of Jena)Eucken and Hodler later fell out, primarily due to their divergent views on the First World War. Despite his cosmopolitan beliefs, Eucken was a fervent nationalist and monarchist who engaged enthusiastically in wartime propaganda.

Eucken travelled extensively, especially after receiving the Nobel Prize, lecturing in Scandinavia, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. In 1912, he accepted an exchange professorship at Harvard University in the USA. Invitations to Japan, China, India and Australia followed, though Eucken was unable to accept them following the outbreak of the First World War. After the war, however, he continued to nurture global contacts. In 1920, for example, the Chinese Minister of Finance visited him in Jena.

Rudolf Eucken left the University and entered retirement in the same year. On 15 September 1926, Eucken died in Jena. Seven years previously, he had founded the »Euckenbund«—an organization in which students and supporters continued to promote Eucken’s ideas after his death, including through a magazine. The family home, which became known as the »Eucken-Haus«, had long since become an international meeting place—with the family moving in 1911 to a new villa at what is today Botzstraße 5. Both initiatives faded gradually following the death of Irene Eucken in 1941 and the couple’s daughter, Ida Maria Eucken, in 1943.