Microalgae are important entities in the structure of life. They fix carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and account for a considerable proportion of global oxygen production. Without microalgae, higher organisms—including humans—could not survive. However, the finely balanced coexistence of microalgae and other microorganisms is increasingly jeopardized as climate change throws environmental conditions out of kilter. A research team led by botanist Prof. Dr Maria Mittag is investigating the processes behind this.

By Stephan Laudien

Microalgae are so tiny that they cannot be seen individually with the naked eye. Nevertheless, they are the living embodiment of the term »global players« because, without microalgae, our planet would be very different. »Microalgae and cyanobacteria are responsible for around half of all global photosynthetic performance, which means they also fix around half of all atmospheric carbon dioxide,« says botanist Prof. Dr Maria Mittag. »At the same time, algae produce a significant proportion of the oxygen on Earth,« she continues, as an expert in these tiny green organisms. These microscopic creatures lay vital foundations for more developed life forms by their production of oxygen.

Microalgae live in freshwater and oceans, in moist soil and even in snow and ice. Occasionally, they multiply in vast quantities to form algal blooms. This often indicates that the usual balance in a body of water is disrupted, such as due to eutrophication. »Microalgae exist in constant interaction with other organisms, usually other microscopic organisms, like bacteria,« says Maria Mittag. These interactions are the subject of research at the University of Jena, including the Cluster of Excellence »Balance of the Microverse«.

Together with organic chemist Prof. Dr Hans-Dieter Arndt and natural products chemist Prof. Dr Christian Hertweck, Maria Mittag has decrypted the symbiotic existence of the green microalgae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and the bacterium Mycetocola lacteus. Their interdisciplinary team has successfully demonstrated that Mycetocola lacteus promotes the algae’s growth. Simultaneously, Mycetocola lacteus protects the alga against attack of another bacterium by rendering the attacker’s toxin inactive. In return, the bacterium receives specific B vitamins from the algae, along with a sulphur-containing amino acid.

This microscopic interaction holds tremendous implications for larger organisms. As one of the initial links in the global food chain, microalgae are essential to life on Earth. This relationship, however, is subject to change. »The algae react to the changing environmental conditions brought about by climate change,« says Maria Mittag. The effects of climate change and rising carbon dioxide emissions include increased carbon dioxide uptake—which is making seawater more acidic. »Some microalgae have a calcareous shell that can dissolve in acidic water,« says Prof. Mittag. As a result, she explains, the composition of species is changing. And, given the rapid momentum of generational succession and unrelenting evolutionary pressure, this change is occurring rather quickly.

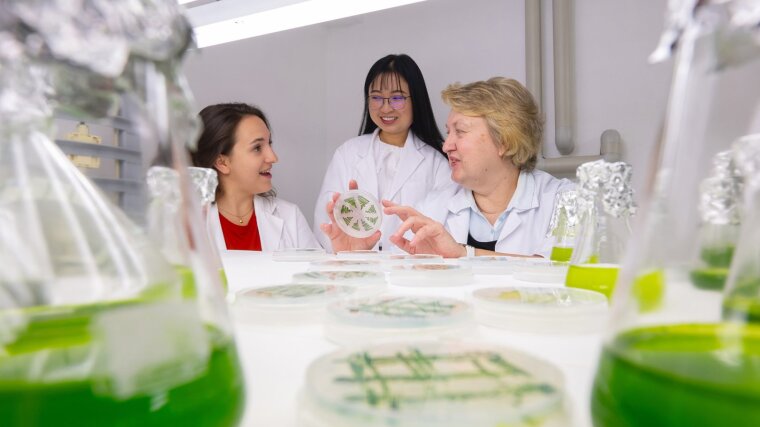

Different strains of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii in agar slant cultures

Image: Jens Meyer (University of Jena)Algae are part of global food chains

In total, Maria Mittag says, there are around 200,000 different types of microalgae, though the true numbern could be much higher. If the volume of microalgae were to fall significantly, it would have implications for the entire marine food chain. Zooplankton feed on tiny algae; zooplankton and phytoplankton in turn serve as a crucial food source for creatures ranging from the smallest fish to gigantic whales.

»This relationship must remain in equilibrium,« says Mittag. The same applies to microalgae in the soil. Human interventions, such as overfertilization and the use of pesticides, can also change living conditions for algae. Nevertheless, Prof. Mittag advises against implementing abrupt measures in an effort to restore balance. »These are exceptionally complex systems in which changes are always subject to feedback loops,« she says. »We are a long way from understanding the fine details of these systems.«

She argues, however, that something evidently must be done to prevent further rises in atmospheric carbon dioxide levels. The biologist emphasizes that we all have a part to play; even choosing not to travel by air is a step in the right direction.

Original publication:

A mutualistic bacterium rescues a green alga from an antagonist, PNAS, 2024; https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2401632121External link