Exploratory drilling projects in Thuringia and South Africa are opening a window into the geological history of the planet. The drill cores obtained in this way are like time capsules that store information from the early days of the Earth. Teams from the fields of geology and palaeontology are currently looking back at different eras of Earth's history, when Thuringia was part of the supercontinent Pangea, and even at the time when life was just beginning. The reportage accompanies them for a while in their work.

By Stephan Laudien

The world must have been pretty quiet 3.2 billion years ago: no birds tweeting, no wolves howling, no crickets chirping… The silence would have been broken only by waves, raindrops, wind, storms and thunder. And who should have made a sound at a time when the only living things were the microbial mats that lined the banks of water bodies? They are thought to have produced oxygen, creating the conditions for more highly developed life.

An international team of geologists led by Prof. Christoph Heubeck from the University of Jena has now unearthed excellently preserved remains of the microbial mats. They are contained in drill cores that are around 3.2 billion years old and were obtained from the »Barberton Greenstone Belt« in South Africa, close to the border to Eswatini, formerly Swaziland. »These drill cores are like time capsules that store information from the early days of Earth,« says Christoph Heubeck.

Libraries from the early days of the planet

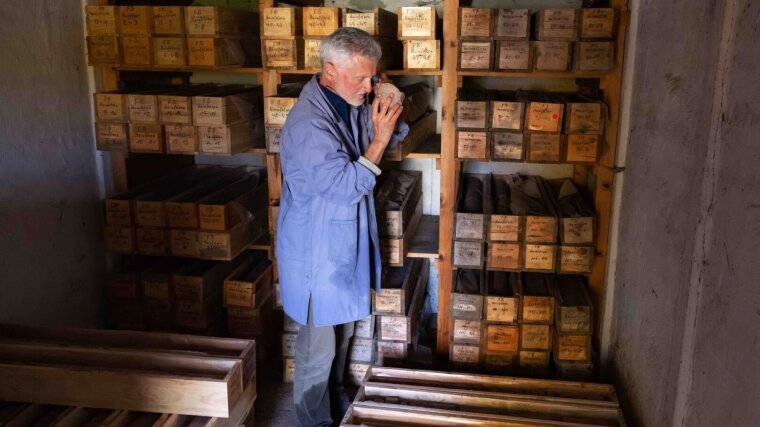

In addition to traces of simple life forms, the drill cores also contain numerous other pieces of information. This allows the scientists to draw conclusions about the lunar orbit and to analyse the tides, volcanism, UV radiation, the intensity of weathering, meteorite impacts and the temperature of the oceans and the atmosphere. The decoratively patterned stone cylinders are veritable libraries from the early days of our planet.

The drill cores are stored in air-permeable boxes made of sturdy spruce wood.

Image: Jens Meyer (University of Jena)Frank Linde sawing a drill core.

Image: Jens Meyer (University of Jena)Carnival atmosphere at the Institute for Geosciences

It's a sunny day in autumn. The grounds of the Institute for Geosciences are bustling with activity. There's a real carnival atmosphere! However, the only thing spinning is the blade of a circular saw as it carefully works its way through drill cores. The machine is operated by Frank Linde, whose focused expression reveals the delicate nature of his work. The technician is wearing safety goggles, gloves and rubber boots.

The »Steinadler« saw works with cooling water, leaving a jet of reddish sludge in its wake. The stone rods are precisely cut open lengthwise to reveal a reddish, marbled interior that shimmers in the sun. However, these drill cores have not been brought to Jena all the way from South Africa. They were drilled near the Bromacker fossil site in the Thuringian Forest. They are around 290 million years old – they date from the early Permian Period.

This is the second major drilling project in which Christoph Heubeck is involved. It just so happens that both projects were carried out almost at the same time last year. In geological terms, the finds near the town of Tambach-Dietharz mark a huge leap in time compared to the samples unearthed in South Africa. They date from the period before the dinosaurs reigned over the Earth, when their ancestors were already leaving numerous traces. These ancestors can be described as being somewhere between amphibian and reptile, including Orobates pabsti and Seymouria sanjuanensis. The latter species had previously been found for the first time in Utah, USA. It was named after the San Juan River, a tributary of the Colorado River. It is no coincidence that the fossils have been found at two different sites; at the time of the supercontinent Pangea, both sites were located on one continent along the northern margin of the Variscan mountain range.

The species Orobates pabsti was named after Wilhelm Pabst, who was the curator at the Ducal Museum in Gotha. He was one of the first people to discover and describe »track slabs« at the turn of the 20th century. These are slabs of rock on which the footprints of primeval animals are preserved. Later, individual bones and even entire skeletons came to light. The most well-known are arguably the »Tambach Lovers«, a pair of Seymouria sanjuanensis immortalized side-by-side in stone for millions of years. Dr Thomas Martens, a geologist and palaeontologist, was the first to discover fossils at the Bromacker site in 1974. The student of Arno Hermann Müller has made studying the Bromacker fossils his life's work. He has even bought the site to secure it for science.

These two Seymouria sanjuanensis specimens are known as the »Tambach Lovers«. They lived on Earth even before the dinosaurs.

Image: Oliver WingsAs soon as the drill cores are extracted from rock, they are measured and precisely labelled. By cataloguing and securely archiving them in this way, they are made available for further investigations, including future generations of researchers. This principle applies to both the drilling project in South Africa and the work in Thuringia. Over the course of the drilling project in the Barberton Greenstone Belt, the diamond core bit drilled down to a depth of 300 metres – often from older to younger layers of rock – at an angle of 45 degrees. »Around 20 to 40 metres of cores were extracted every day,« says Christoph Heubeck. In Thuringia, the drilling depth increased by eight metres every day until around 250 metres depth had been reached.

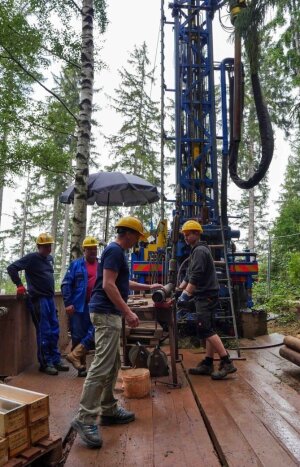

The drilling itself was essentially routine work. The geologists had originally identified a spa hotel's car park as the most promising drilling site. As the hotel did not close in the winter, however, another site had to be found. »We ended up drilling in the forest, right next to a forest road,« recalls Christoph Heubeck. The only sour note for the contracted company came when the drill bit broke off at a depth of 243 metres and had to be replaced.

A large core drilling rig was the main exploratory tool used in both projects. »In terms of approach, this is not much more than a magnifying glass or a hammer,« says Christoph Heubeck. »It's not so much the size and type of equipment that matters, but a smart choice of research question, the best possible location for carrying out the work, efficient data acquisition and optimal evaluation«.

As the sedimentary rocks that provide information about the Earth's geological past are usually covered by younger layers, weathered soils and vegetation, core drilling is often the method of choice for extracting unweathered and continuous material, which can then be »interrogated« in the laboratory.

This opinion is clearly shared by those involved in the International Continental Scientific Drilling Program (ICDP), the main funder of the South African project. That's why a major conference on the future of scientific drilling will be held in Potsdam in July 2023.

The first insights emerge even as the drill cores are being cut open. On first inspection, Christoph Heubeck points at blue-grey lumps in the drill core: »Those are carbonate nodules. Their isotopes act as a paleothermometer«. This means that the researchers can use these lumps to analyse what the temperature was like when the mineral formed. In this way, statements can be made about the climatic conditions of prehistoric times and comparisons can be made with today's conditions.

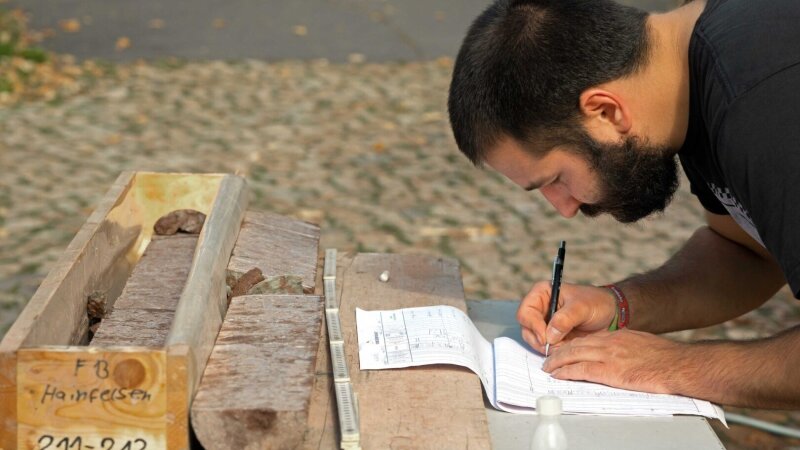

Student Fabio Berlin records data from the freshly cut and washed drill core.

Image: Jens Meyer (University of Jena)Rig used for deep geological drilling on the Hainfelsen rock face near the Bromacker site.

Image: Claudia HilbertFossils in former quarry

The Bromacker site near Tambach-Dietharz paints a rather unassuming picture these days: a meadow, sparse trees, hiking trails and information boards… But it used to be home to one quarry after another. The mining work revolved around »Rotliegend« strata (»Underlying Red«), a type of red sandstone that was used as a building material for things like gate stones, fence poles and veneers. Some of the former quarries are still fairly recognizable today - dangerous areas are highlighted by warning signs.

Dr Anna Pint knows the area like the back of her hand. The geologist and palaeontologist from Prof. Heubeck's research group has been digging at the Bromacker site since 2020. She specializes in invertebrates and burrows. »We've found fossils of insects, crustaceans and a few centipedes,« says Anna Pint.

The current Bromacker project is a collaboration between scientists from the Natural History Museum in Berlin, the University of Jena and the Friedenstein Castle Foundation in Gotha. The digging campaign takes place every summer. About 20 people are involved, including numerous students and doctoral candidates. Their tools are hammers and chisels – large pieces have to be smashed up. As a member of the excavation management team, Anna Pint decides which finds are promising. The rest remains in the overburden. The finds are analysed by the relevant specialists. If vertebrate bones are found, they are placed in the hands of Tom Hübner – the curator of the Friedenstein Castle Museum – and Jörg Fröbisch from the Natural History Museum in Berlin, who is also in charge of the overall Bromacker project.

Footprints of the dinosaurs' ancestors

Lorenzo Marchetti is another expert from the Natural History Museum in Berlin; he is responsible for examining the footprints of the dinosaurs' ancestors preserved in the rock. As long as the finds are still moist, they can be processed. For this purpose, Frank Linde prepares »thin sections« of the burrows in Jena. These are wafer-thin slices that can be viewed under the microscope. When held up to the light, you can clearly make out the tunnel that was dug out by an insect millions of years ago.

Other finds have to be carefully dried. Once they have been dried, they cannot be exposed to any more moisture. »The clay contained in the samples would swell up and fragment the pieces,« explains Anna Pint.

Drilling rig and crew in South Africa.

Image: Christoph HeubeckThe drilling in South Africa was mainly funded by the International Continental Scientific Drilling Program (ICDP), a consortium comprising 21 member states. A total of 1.8 million euros was raised for the drilling costs – and several times that amount went towards funding the investigations and paying the wages of doctoral candidates and post-docs involved in the project.

Even the US space agency NASA is involved because 3.2 billion years ago, the surface of the Earth resembled that of other planets. »How could life survive and spread in this challenging, high-energy environment?,« asks Christoph Heubeck. An average sedimentation rate of around one metre per thousand years can be estimated in the drill cores. This is similar to the sedimentation rate observed on many of today's coastlines, although daily tides are often recorded in thin layers of sediment as well.

The scientific evaluation of the drill cores will not take anywhere near as much time. Nevertheless, it will take a few years before these time capsules from the early days of Earth will have been comprehensively examined and analysed, says Christoph Heubeck. Firstly, they are sawn lengthwise, photographed and described. Then one half was trucked to South Africa's national core repository, effectively a »library of the underground«; the other half has been shipped to the ICDP's core repository in Berlin-Spandau, where they are currently X-rayed, documented again in detail and distributed to the participating research institutions during a sampling workshop.

The area around the Bromacker site once resembled the landscape of today's Mongolia, as noted on one of the information boards. Anna Pint explains that it was a sedimentary basin; the sandstone was laid down in rivers that crossed the area. The aim now is to create an exact scientific reconstruction of the habitat found in this distant period. »We're looking through a window into the past and exploring a section of the Earth's history,« says Anna Pint. By »we« she means Christoph Heubeck and his team: Thomas Voigt, Frank Linde, Peter Frenzel and Anna Pint, as well as the students Jakob Stubenrauch, Rebecca Lellau and Fabio Berlin. The group from the University of Jena is the smallest in the Bromacker project, which was launched in 2020 and is scheduled to run for five years.

apl. Prof. Peter Frenzel and Dr Anna Pint at the Bromacker excavation site.

Image: Claudia HilbertFinds belong to the State of Thuringia

The Bromacker site may apply for UNESCO World Heritage status. This status would represent a promotion to the »big league« including the Messel pit in Hesse or the Solnhofen site in the Altmühltal Nature Park in Bavaria, where famous specimens of the primeval bird Archaeopteryx were found. If the Bromacker site is granted this status, it will be fenced off and secured, if only to deter robbers. The fossils already belong to the State of Thuringia. Anything that is not exhibited in the museum collection at Friedenstein Castle is stored in the depository there.

Anna Pint points out that most of the fossils found belong to herbivores. However, it is difficult to say what they ate, because plant fossils are rare among the finds, but this could also be due to the unfavourable conditions for preserving them. Nevertheless, the researchers want to reconstruct these animals' habitat, their food and the climate of the time in as much detail as possible. The window into the past will be thrown wide open. As wide as possible.