The crew of the French research vessel »Tara« is sailing along the coasts of Europe until mid-2024, collecting thousands of water samples in an effort to decode the language that microorganisms use to communicate in water. Doctoral candidate Maïa Henry of the University of Jena has been on board for part of the voyage.

By Ute Schönfelder

The 36-metre-long, two-masted schooner »Tara« docked in Amsterdam in April 2023. Its current mission—»TREC: Traversing European Coastlines«—is scheduled to end in Malta in mid-2024.

Image: Margault Demasles – Fondation Tara OcéanTiny creatures of huge significance

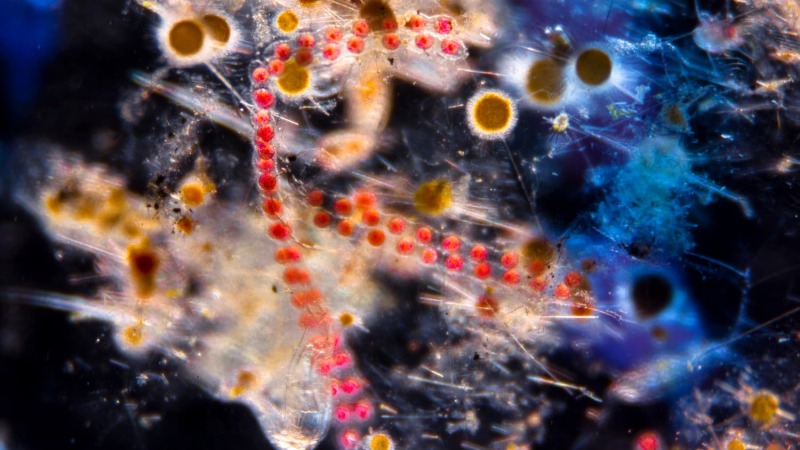

Microplankton are microorganisms, including bacteria and microalgae, that drift in water and play a vital role in the Earth system, producing a significant proportion of the oxygen in our atmosphere. But that’s not all: they also create the building blocks for reefs and coastlines and, as part of the food chain, provide the basis of existence for marine animals, thereby laying the foundations for the fishing industry.

Since April 2023, an international research team has been working on a survey project of vast scale: researchers aboard the schooner »Tara« are sailing along more than 25,000 kilometres of European coastline to collect water samples. In parallel with this, samples are also being taken from the soil and shallow waters along the coast. This expedition—titled »TREC: Traversing European CoastlinesExternal link«—aims to index all lifeforms in the water, sediment, soil and air along European coasts in order to facilitate a detailed understanding of the interactions and biological functions that connect species and ecosystems. The researchers also hope to examine the impacts of chemical pollutants and climate change on biodiversity in marine environments.

The European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) is coordinating the expedition in collaboration with over 70 scientific institutions. Around 150 researchers from roughly 30 countries are involved in the undertaking, including Prof. Dr Georg Pohnert of the University of Jena, who is one of the project leaders.

Microscopic image of a plankton community.

Image: Christian Sardet, Fondation Tara OcéanSea sickness and shift work

Early career researcher Maïa Henry has also spent time on board »Tara«. The 24-year-old is working on her doctoral thesis as a member of Pohnert’s team, which is part of the »Balance of the Microverse« Cluster of Excellence. Henry’s research, which focuses on the metabolism of marine microorganisms, involves analysing the chemical substances these organisms emit in certain environmental conditions.

She worked as part of the research crew aboard »Tara« during two stages: from Ostend in Belgium to Aarhus in Denmark, and from Galway in Ireland to Bilbao in Spain. For the entire two months, Maïa Henry—like the other 14 members of crew—worked shifts to conduct her research. However, the duties extended far beyond that: besides collecting and preparing water samples, the team communicated their research to school groups and the wider public, and were also responsible for day-to-day operations, from washing dishes to the night watch.

The crew of the »Tara« work around the clock, seven days a week. Their shift schedule is determined by the tides, so while shifts sometimes start at 8am, others start at 4am. Seasickness—which also proved an issue for Maïa Henry, who had no previous sailing experience of any kind—is no excuse. Everyone on board has a vital role to play.

Submerged

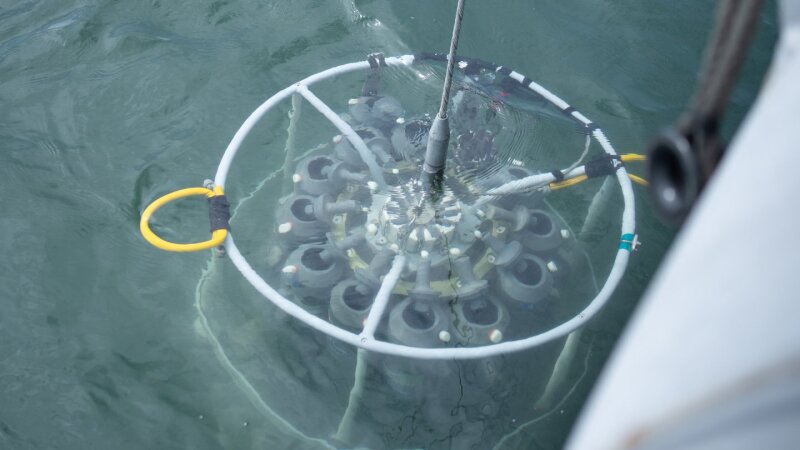

A rosette sampler is a submersible device capable of collecting samples from different depths of water. It is equipped with a number of sensors that measure a variety of parameters simultaneously, from salt and oxygen content to pressure and temperature.

In addition to this device, the sailing vessel has a range of nets. These include a »Manta« net, which can capture objects floating on the surface, such as plastic waste, and plankton nets, which can capture small organisms at depths of up to 700 metres and bring them to the surface. Changing the mesh size enables the nets to collect different types of plankton. In addition, the team collect water samples from the surface as well as aerosols from above the surface, which can also contain bacteria and viruses.

The water samples are processed while on board. They are pumped through filter cartridges in a multi-stage process, which increases the concentration of the organisms and substances in the water. The samples are then frozen at –20°C and transported to land-based laboratories participating in the project.

A rosette sampler, which collects samples of plankton at different depths.

Image: Margault Demasles – Fondation Tara OcéanSearching for chemical traces in the lab

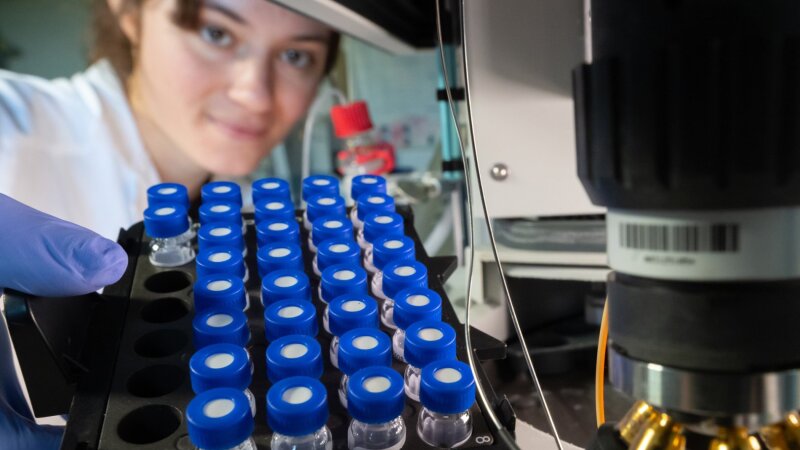

Back on dry land, the thousands of collected samples are extracted and concentrated in the course of further processing. The next step in their analysis involves liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). Each sample passes through a column in which the individual components of the sample are separated depending on their interactions with the column material. The chemical compounds are then transferred into the mass spectrometer, where they are ionized and analysed depending on their mass-to-charge ratio. The resulting mass spectra are compared against databases, which makes it possible to identify the chemical compounds in the original sample.

The research team is particularly interested in the metabolic products that marine microbes generate, which can provide resistance to certain stress factors. One example is the »ectoine« molecule, an osmolyte that protects certain species of plankton against environmental stresses such as temperature fluctuations and high salinity levels.

Researchers are also collating their data on the chemical composition of plankton communities with insights from other research groups to form an oceanographic map of microorganisms and their chemistry. This data will pave the way for a better understanding of microbial dynamics in the oceans.

Back in the lab at home: Maïa Henry examines water samples.

Image: Jens Meyer (University of Jena)