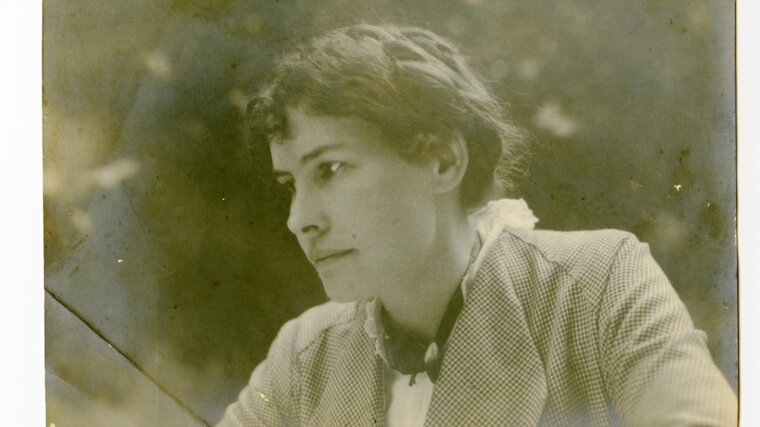

A century ago, in the autumn of 1923, Mathilde Vaerting became the first woman to become a full professor in Germany when she was appointed at the University of Jena. Yet, she was repudiated by her colleagues—first and foremost because she was a woman.

By Sebastian Hollstein

The first woman to be made a full professor at a German university: what might sound to us today like a significant societal event and a historical turning point proved a tremendous, lifelong burden for Mathilde Vaerting. Upon her arrival in the winter semester of 1923/24, the University of Jena and its professors did not welcome her with open arms, but showed the proverbial cold shoulder. Entitled »Childcare for Cultural Evolution«, her inaugural lecture should have been cause for celebration. But instead of the ceremonial surroundings of the assembly hall, she gave her speech in a small lecture theatre, on a Saturday morning, without the wider public taking any notice. Why exactly did her appointment encounter such resistance?

Johanna Mathilde Vaerting was born in 1884 to a prosperous farming family in Emsland, Lower Saxony. One of many siblings, she studied mathematics, physics, philosophy and Latin in Bonn, Munich, Marburg and Giessen. In 1911, she received her doctorate in the field of philosophy in Bonn. After completing her studies, she worked as a teacher in Berlin, conducted research in her spare time and took classes in medicine and sociology.

Gender plays no role in education

Already at an early stage, Mathilde Vaerting’s research scrutinized established doctrine and teaching practices: she attacked rote memorization as a teaching method and advocated equal status for teaching staff and students. Over time, she increasingly devoted her attention to a field of research that barely existed at the time: gender studies.

Vaerting emphatically stated that gender plays no role in education. She contended that girls are no less capable in scientific subjects than boys: any differences were merely the result of different positions of social power, while alleged gender-specific characteristics were the result of power relations. By combining pedagogical, psychological and sociological approaches, she paved the way for new scientific issues.

The thesis she submitted to the University of Berlin for her postdoctoral lecturing qualification (Habilitation) in 1919 was rejected, not least due to reservations about the field of research. Despite this, the published version of her thesis—entitled »A New Basis for the Psychology of Man and Woman«—achieved renown and recognition, possibly turbo-charging her academic career. In 1923, the Thuringian Minister for Public Education, Max Greil, appointed Vaerting as a Professor of Pedagogy at the University of Jena as part of extensive reforms to the Thuringian education system.

The University’s leadership, however, saw the move as an attack on the institution’s autonomy—especially as this was the first time a woman was appointed to a full professorship. Vaerting’s colleagues claimed that she lacked the professional ability for the role. Ludwig Plate, a zoologist and anti-Semite, even published a diatribe about her, entitled »Feminism under the Guise of Science«. Peter Petersen, who Greil also appointed to a position in Jena, encountered considerably less resistance and consolidated his position at the University—at Vaerting’s expense.

When the National Socialists seized power in 1933, Vaerting lost her professorship and was excluded from working at the University. She decided to move back to Berlin. A ban on leaving Germany prevented her from accepting appointments to universities in the Netherlands and the USA. Meanwhile, a ban on publications prevented her from continuing her academic work.

Even after World War Two, she was denied the opportunity to return to university work. She turned her attention to state sociology but was unable to gain a foothold in the academic sphere. Mathilde Vaerting died on 6 May 1977 in Schönau im Schwarzwald. In the 1990s, however, her work began to garner renewed attention. Today, she is regarded as a little-known but highly significant pioneer of an educational theory that takes account of social power relations and the impact of categories of difference.

In 2023, a memorial plaque commemorating Vaerting’s appointment was unveiled in the University of Jena’s Main Building. Furthermore, the Society for the Study of the History of Democracy (Gesellschaft zur Erforschung der Demokratiegeschichte, GEDG) partnered with the University to publish a comprehensive brochure on the life and work of the first woman to be appointed to a full professorship at a German university.