Glasses are commonly known as transparent materials. For example, glasses in façades enable the interior of buildings to be illuminated by sunlight, while glass vessels allow to check their contents. However, Dr René Limbach and his team are investigating completely different types of glasses – made of opaque metals.

By Marco Körner

»Metallic glasses aren’t transparent«, says Dr René Limbach. They even look the same as ordinary metals: silvery-grey and shiny. According to the engineer from the Otto Schott Institute of Materials Research, these materials are yet very different in terms of their mechanical properties: Metallic glasses are very hard, strong, and wear resistant. These attributes make them suitable candidates for applications as structural materials in gears, drive shafts and protective coatings. »Wherever there is friction between components, metallic glasses can be used to reduce wear and tear«.

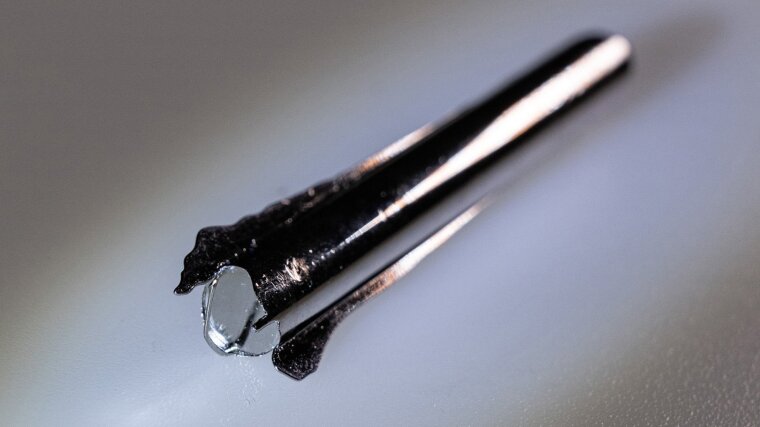

But what exactly is a metallic glass? Dr René Limbach describes the fabrication process: »To vitrify a metal, its melt has to be cooled extremely fast«. This is often done by suction casting into »moulds«: Water-cooled hollow cylinders with a double wall made of materials of high thermal conductivity, such as copper. The metallic melt is poured into the cavity, causing it to freeze-in very rapidly. This requires ultrafast heat extraction, which restricts the dimensions of metallic glasses – typically about two to three millimetres in diameter with lengths of up to around five centimetres.

The engineer describes how metals are transformed into glasses: »Thanks to the rapid cooling, the metal solidifies in the mould without the atoms having enough time to rearrange themselves in an ordered crystalline structure. Good glass-forming alloys are multi-component systems with significant atomic size differences«. This results in a highly disordered structure upon solidification. »The material still exhibits a short-range around the individual metal atoms but no long-range order within the material as a whole. Such an amorphous structure is inherent to glasses».

However, the absence of long-range order also results in a major disadvantage for metallic glasses: They are extremely brittle, admits Dr René Limbach. He is searching for strategies to overcome this drawback.

»In crystalline metals, the atoms are arranged in a well-defined lattice structure. An external interference can easily be dissipated through the lattice. In amorphous metals, on the other hand, shear bands are formed, which propagate through the material without hindrance, eventually leading to fracture«.

Current strategies to neutralize the propagation of shear bands rely on the creation of microstructural features by means of phase separation or the presence of crystalline precipitates.

A completely different approach is considered by Dr René Limbach in collaboration with researchers at the Leibniz Institute for Solid State and Materials Research Dresden: »We use thermal and mechanical processing routines to increase the number of shear bands formed, which then interfere each other«. For this purpose, structural units of lower mechanical stability are introduced, thereby increasing the structural heterogeneity. By doing so, the number of shear bands created, and their interactions are maximized. This in turn enables plastic deformation and accompanied by this, an increased service life before fracture occurs.

From curiosity to functional alloys

»Transferring this material to application would obviously be the Holy Grail«, explains the engineer. »Metallic glasses were originally a curiosity. Scientists were initially asking themself: Can metals exist in a glassy state? Indeed, metallic materials can be transformed into glasses, and they exhibit an interesting set of mechanical properties. But the brittle fracture behaviour restricts a widespread use«. If this problem can be solved, metallic glasses could replace numerous structural and functional alloys, adds Dr René Limbach. At least on a small scale: »Metallic glasses still have very limited dimensions due to the way they’re fabricated«.