Caspar David Friedrich (1774–1840) enjoyed tremendous success during his lifetime but went out of fashion in his later years. His works were only rediscovered in the 20th century. A new project launched by Prof. Dr Johannes Grave is looking to publish a comprehensive, critical and commented edition of Friedrich’s writings.

Interview by Irena Walinda

Mr Grave, what is your project all about?

It is about all the texts and writings in which Caspar David Friedrich expressed himself. Most of the writings are already known and have been printed, but many of them do not meet academic editorial standards—with the exception of the majority of his letters.

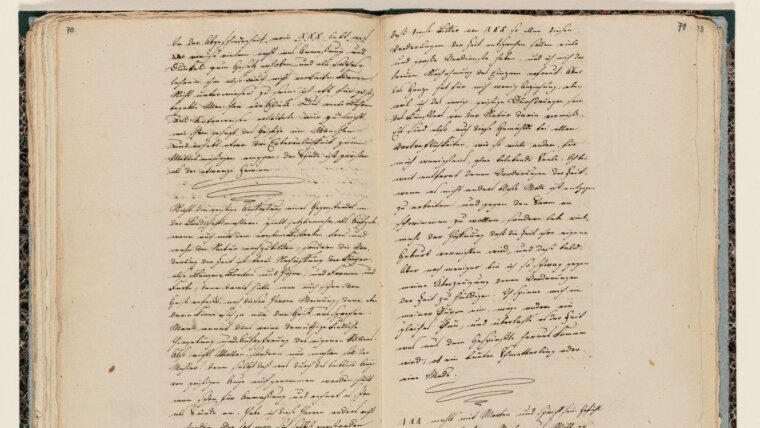

Take, for example, the manuscript with the somewhat cumbersome title »Comments on a Collection of Paintings by Mostly Living or Recently Deceased Artists«, in which Friedrich comments on numerous pictures painted by his contemporaries. Here the painter becomes an art critic, which is obviously exciting. Although researchers have long known that many of the paintings discussed must have been created by his contemporaries from Dresden, several others are yet to be clearly identified, because Friedrich anonymizes the artists instead of naming them. We hope to make some progress here. It is also worth pointing out that the manuscript has been printed several times, but it has never been correctly edited from an academic perspective. The orthography has been standardized, the order of the paragraphs is questionable, and certain words and phrases have even been omitted in places. Above all, there is no in-depth commentary that explains individual terms, points out relationships and tentatively identifies as many of the people and works mentioned as possible.

Whose work could this animal painting be? The dog is splendidly painted, as if by XXX, but the fellow who is leading the dog looks as if the dog has painted him.

Caspar David Friedrich in his »Comments on a Collection of Paintings by

Mostly Living or Recently Deceased Artists« (mainly around 1830).

What do you and your team want to do differently?

For this manuscript and other texts such as his short writings, poems, prayers, diary entries and letters, we are following strict, uniform and academically correct standards to develop an edition that faithfully reproduces Friedrich’s remarks—with all the apparent inadequacies in spelling and punctuation and with detailed comments. Our aim is to emphasize the value of these textual sources and provide a new basis for research.

Why is an edition so important for current research?

These writings could be important when it comes to researching the painter’s works. For example, many Friedrich scholars believe the painter wasn’t particularly well educated—more naïve than intellectual. Many assume that he was simply able to express himself differently in his paintings. But if we take a closer look at his writings, we can discover a thoroughly complex, sophisticated and even intertextual use of language. The texts can help us gain a better understanding of Friedrich’s paintings and the artist himself.

Can you give an example?

The inadequate examination of Friedrich’s texts has led to false assumptions and conclusions. For example, Friedrich has been degraded as coarse and crude for using the term »in Verschiss gekommen«, an expression that alludes to the German word for »shit« and essentially means »out of fashion«. However, such expressions are also found in Goethe’s writing. So, it isn’t as scandalous as it might sound at first. Here is another example: Some art historians have seen Friedrich’s spelling mistakes and incorrect punctuation as an indication of his poor education. But I challenge you to find someone who got that consistently right around 1800. You will be looking for a long time.

Where are the letters and writings kept and/or shown?

The manuscript »Comments on a Collection of Paintings« is currently housed in the Kupferstich-Kabinett (Collection of Prints, Drawings and Photographs) in Dresden. All sorts of smaller texts have been sourced from Caspar David Friedrich’s estate. A substantial part of the manuscripts now belongs to the Saxon State and University Library in Dresden. The letters can be found in many different places. Many of them have been bought by the Pomeranian State Museum in Greifswald, most of which are letters addressed to his family. Friedrich was originally from Greifswald, and he often wrote to his brothers. But as is the case with letters, they are often found in the recipients’ estates.

Do the letters addressed to his family tell us something about what Caspar David Friedrich was like as a person?

Yes, of course. For example, one letter from 1808 clearly shows how much Friedrich disliked the French, who occupied Saxony under Napoleon at the start of the 19th century. In the letter, he asks his brother, who was staying in Lyon at the time, not to write to him again until he had crossed the border. Friedrich makes it quite clear that he doesn’t want to receive any letters from France.

In another letter, he implies that he is afraid his letters are being opened and read by the authorities. That is plausible and not without its dangers, especially as Friedrich occasionally took a stance on political issues. In fact, one of Friedrich’s letters even became the subject of an interrogation involving Ernst Moritz Arndt in 1821.

Some of Friedrich’s pieces of writing that are most interesting for research include the letters and enclosures in which he discusses his own paintings such as »The Cross in the Mountains« (one of his first major works) or the famous »Monk by the Sea« and its counterpart »The Abbey in the Oakwood«.

In another, he offers a slightly humorous description of his new life as a husband after marrying later in life. »Ever since the I became We,« he wrote to his relatives in Greifswald in January 1818, »a good deal has changed«. Now, when hammering a nail in place, he had to make sure he didn’t position it too high up, so that his wife could reach it. So, Friedrich wasn’t just the stern and grumpy painter that he is sometimes made out to be. He had quite a sense of humour.

Prof. Grave is carrying out his editorial project entitled »The Writings of Caspar David Friedrich and His Dresden Contemporaries« with the proceeds from the Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Prize, which he won in 2000. He is cooperating with the Kupferstich-Kabinett as part of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen (State Art Collections) in Dresden. Prof. Grave is working on the project alongside Dr Petra Kuhlmann-Hodick and PD Dr Johannes Rößler.