By Ute Schönfelder

The sea or a sunset, a mountain backdrop or a candlelit dinner—when something is particularly beautiful, particularly emotive and charged with positive expectation, it will almost always elicit exclamations of: »How romantic!« Hardly any other period in literary history has immortalized itself in everyday language with as many clichés as Romanticism. And there is hardly any other period about which so many misconceptions still prevail today.

»For example, there is still the idea of the ›dark abysses of the German soul‹ and that these have something to do with Romanticism,« says Prof. Stefan Matuschek. The cliché of the irrational, romantic German soul persists and is said to stem from the shock of the post-war period, in light of the extent of the National Socialists’ crimes. »The atrocities of the Nazis were so huge that it was difficult to explain them only on the basis of a government’s actions over a few years, which is why German history was examined in search of a breeding ground for these events.«

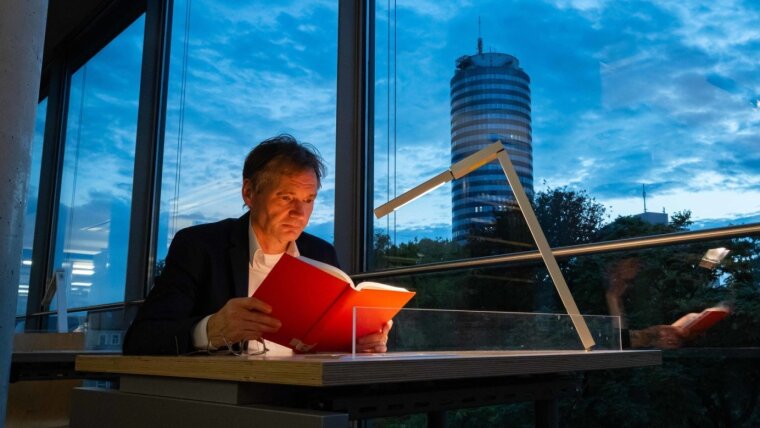

The Nazi’s crimes as the final consequence of the romantic nationalization of the Germans? This myth, often repeated to this day, is just as untenable as the claim that Romanticism was a counter-movement to the earlier Enlightenment, says Matuschek. The Jena-based expert on Romanticism attempts to dispel such misconceptions in his book »Der gedichtete Himmel. Eine Geschichte der Romantik«External link (»Poetic heaven. A history of Romanticism«). This volume of almost 400 pages is explicitly aimed at a non-specialist audience and takes a new, contemporary look at the era that has been so misunderstood up to now.

It quickly becomes clear from reading the book that Romanticism is a European phenomenon and that Germans are by no means particularly ›romantically inclined‹. »In addition, the differentiations in European Romanticism do not necessarily run along national borders, but are instead determined by social milieus and periods of history,« says Matuschek. Whereas in Germany, Jena’s Early Romanticism as an academic avant-garde argued about Kantian philosophy with the established Enlightenment philosophers, in France and Italy, Romantic authors countered the established academic high culture with folk narratives. »So, when we speak of Romanticism, we may mean quite different European developments,« adds Matuschek.

What is common to all Romantic literature, says Matuschek, is that it answers questions that the Enlightenment left unanswered or brought into the world in the first place. Questions on subjects such as the meaning of life or what perspective there is after death are of central importance to modern humans, but there can be no empirically verifiable answers to them. Instead of diverging into a fateful irrationalism, the legacy of Romanticism is to offer humans a method for using their imagination to answer these questions and to build »imaginary castles in the air«, and, in doing so, to realize—in an enlightened way—that they are just castles in the air. Instead of being a counter-movement to the Enlightenment, Matuschek’s message is that Romanticism is a progressive movement that shapes modern consciousness with its own independent creation of meaning just as much as the Enlightenment itself.

Matuschek’s book shows how Romanticism not only breaks new ground in literature, but also influences the visual arts, music, science and politics. Above all, however, it is a vivid foray through the varied literature of Romanticism: from Novalis’s »Blue Flower«, through the »Romantic classics« Goethe and Schiller, from the world-weary literature of Chateaubriand and Lord Byron, through the »fragments« of Jena’s early Romanticism, to the fantastic tales of E.T.A. Hoffmann, the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm and the Gothic Romanticism of works such as Mary Shelley’s »Frankenstein«.