Romanticism favours »as well as« approach over »either or«

Caspar David Friedrich is one of the most important painters of German Romanticism. What can his wild, mist-shrouded landscapes and the people in them tell us today? Our author gained an impression of this in an interview with art historian and Friedrich expert Johannes Grave.

By Marco Körner

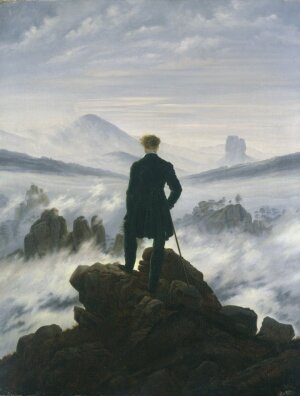

The wanderer above the Sea of Fog, painted around 1817 by Caspar David Friedrich.

Image: bpk / Hamburger Kunsthalle / Elke WalfordA man in an old-fashioned-looking dark green frock coat stands on a brown rock formation. He is leaning on a walking stick and looking down on mountains shrouded in fog. What I see in the picture does not exist in reality, Prof. Dr Johannes Grave explains to me as we talk about the painting »Wanderer above the Sea of Fog« by Caspar David Friedrich. This, precisely, is one of the messages of Romanticism, as I come to understand better in the course of our conversation. The questions from this artistic period that art historian Grave is grappling with are particularly relevant to us today, at a time when we are changing nature to an unimagined extent.

Composed imagery instead of a reproduction of reality

Caspar David Friedrich painted his »Wanderer« around 1817. The entire painting is composed. »The two darkly protruding mountain slopes on the right and the left meet exactly in the centre of the picture, where the person is standing looking at the landscape,« describes Grave. A rock formation on the right of the landscape recalls the shape of the wanderer’s head. »There was clearly an organizing hand at work in this seemingly untouched natural scene.« In other words: Friedrich made use of precise studies of nature, but he simply made up their composition. And what is more: »Friedrich clearly emphasized this imagery, that is to say, the difference from reality,« says Grave. Okay, I say to myself. A picture of a landscape is not a landscape. And what is realistic about a painted landscape anyway?

The conversation with Grave about this painting, which is more than 200 years old, sparks questions about the relationship between humans and nature that are still valid in the present day. After all, we’re changing our environment to such an extent that the current epoch of our planet is called the Anthropocene—the Human Age. How we deal with this is one of the most important questions of our time.

»On the one hand, humans are part of nature, but at the same time they can reflect nature and see themselves as its counterpart,« Grave explains. »Romanticism is perhaps the first movement to consistently scrutinize this relationship.«

At the same time, he warns against viewing the Romantics from this contemporary perspective merely as early environmentalists. »Novalis, one of the leading Romantic poets, worked in the mining industry. And at that time, hardly anyone thought that people could interfere with nature as much as we do today. What the Romantics did was to reflect on the ambivalent relationship between humans and nature. They asked questions such as: what does it mean that on the one hand we are unquestionably part of nature, but on the other hand our ›spirit‹—to use a term from around 1800—can be understood as being the opposite of nature? How should we think about the unity—and at the same time the difference—between nature and spirit, and what are the consequences of this for our dealings with nature?«

Such questions continue to move us today. »In dealing with the climate crisis, for example, there is a type of solution that I would call technological and instrumental,« says Grave. »In this approach, the human being is seen as a mastermind, the sovereign homo faber who actively changes his environment according to his own ideas and who only has to make certain technical adjustments in order to do so. However, the image of Goethe’s ›Sorcerer’s Apprentice‹, who sets in motion a process that he can ultimately no longer control, would perhaps be more appropriate. Romanticism reflects our position in nature and the great extent to which everything is intertwined. It moves away from limiting itself to single, empirically provable causalities to acknowledge virtually infinite interactions.«

Dual perspective – observing the observer

I notice that when I look at the »Wanderer above the Sea of Fog«, I actually see not so much the landscape, but the person who is standing in front of it and is at the same time part of it. »That is the aim of the picture,« says Grave. »The painting is often interpreted in such a way that we are supposed to identify with the observer and experience nature as an occasion for sublime experiences. But that misses the real point of the painting.«

While I want to look at the landscape in the painting, I realize that the person depicted is not only blocking my view—ultimately, that person is what I’m looking at. Now it is clear to me that the deliberately composed lines in the painting are meant to direct my gaze to that very person. »I become the observer of the observer,« is how Grave describes my experience.

The ruggedness of the landscape reminds me of images of open-cast lignite mines and people standing in them or on the edge of the pit to draw attention to the harmful consequences of coal mining for the environment and the climate. These pits are man-made, but not designed according to aesthetic criteria. Grave agrees with me on one point: »An open-cast lignite mine has something excessive in its dimensions; it shares that with nature, insofar as nature appears sublime, because it is not attuned to us in size and dimensions. And experiences of the sublime such as these greatly fascinated contemporaries around 1800, especially the Romantics.«

Grave makes it clear that the comparison with open-cast mining is nevertheless misleading: »The images created by climate activists in open-cast mines follow a completely different logic, namely the laws of political communication. In that case, it is about an emphatic signal; an unambiguous message is conveyed. Romanticism instead emphasizes ambiguities, multiple meanings.«

In his estimation, the ability of the Romantics to deal with ambiguities also enables them to take a critical look at an unrealistic naivety, which he suspects exists at least in parts of the climate justice movement. »There sometimes seems to be an ideal expressed there that we should only intervene in nature as little as possible. But we are now in the Anthropocene. And there is also no going ›back to nature‹, because the traces we have left up to now cannot be erased and nature as such is constantly changing.«

Alternatives to the here and now—Romanticism creates new scope for reflection

Romanticism therefore does not mean idealizing nature in its supposedly pristine state, but rather dealing with our relationship to it, says Grave. »This is also true of our relationship to the past. Romanticism can be understood as the first modernist movement to reflect critically on its own new era in a very fundamental sense. If Romanticism looks back to the pre-modern era, it is not in order to search naively for an ideal state there. It is more that in this way, it can think of alternatives to the present—in the knowledge of what went before. In this way, it opens up new scope for reflection.«

At a time when many decisions for managing the crisis are ostensibly without alternatives or alternatives seem to be mutually exclusive, Grave considers a critical view in the spirit of Romanticism worth considering: »Instead of ›either or‹, it would favour ›as well as‹. This is precisely why the medium of the picture lent itself to this, because a painting of a landscape is always both landscape and painted canvas.«

To a certain extent, Romanticism can enable us to train ourselves in two areas: our own tolerance of ambiguity and our willingness to reassess those otherwise tacitly assumed preconditions that have always directed our gaze and our thinking.